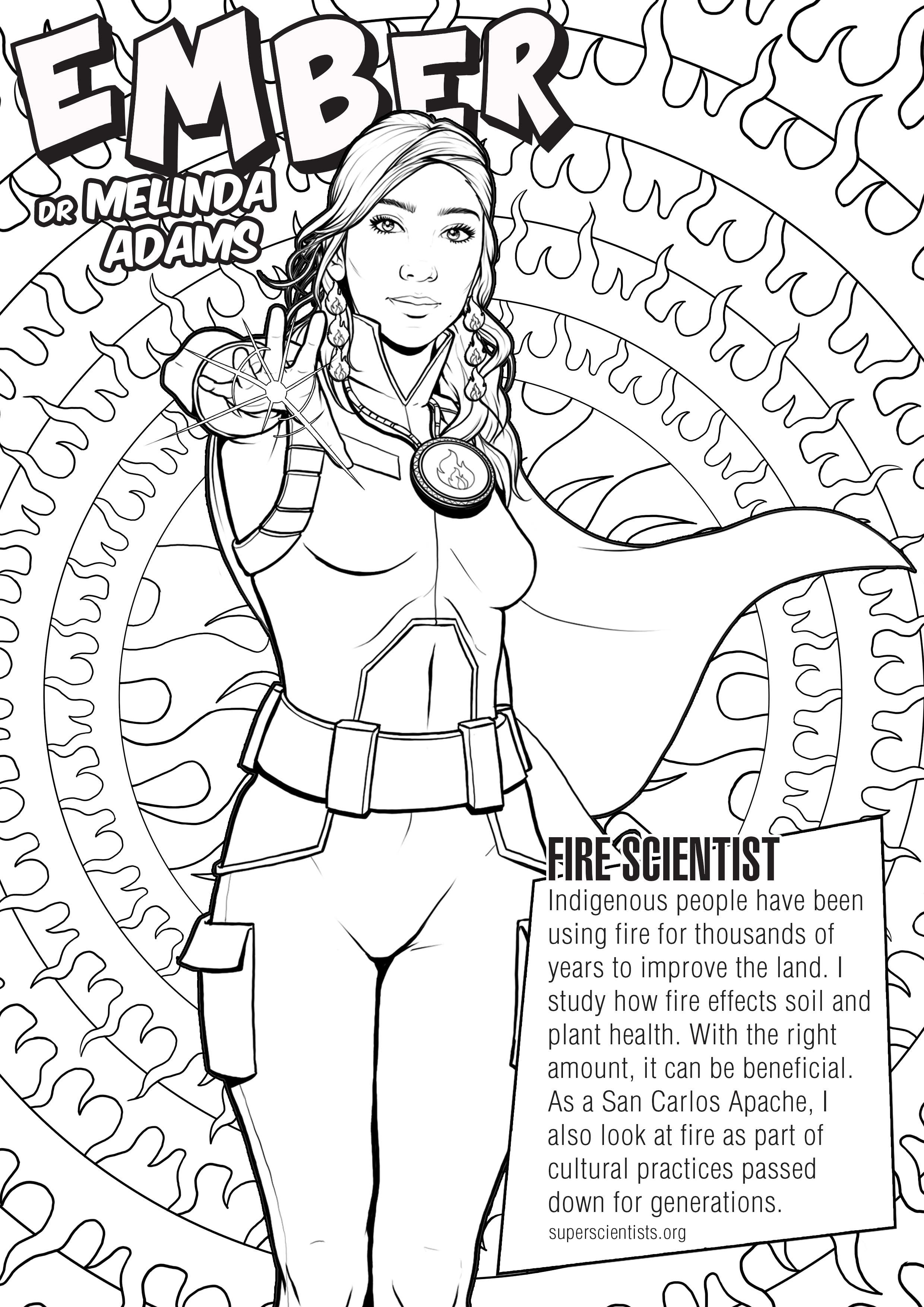

Ember - Melinda Adams

Dr Melinda Adams - Fire Scientist; Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas, in the Department of Geography and Atmospheric Science, and the Indigenous Studies Program. #goodfire #culturalfire #Indigenous #NativeAmerican #wildfire

Her Research: Think of the aftermath of a fire in nature - the ash, the blackened skeletons of bushes and trees, the ground bare of the grasses that were once there. It seems like it’s incredibly destructive and in some ways it is. But wait a week after a fire and new grasses will be sprouting, wait a year and you might have a lush meadow where there was none before.

Fire is part of nature and ecosystems and plants have evolved with it. Fire clears away bushes for grasses to grow, the ash is full of nutrients that were locked away in leaves and branches, the heat of fires is even necessary for some plants to release their seeds and make the next generation. Fire is part of the circle of life in a healthy ecosystem. You’ve probably seen massive wildfires on TV and those are NOT so healthy. In many of those situations, we stopped fires that could have been helpful, so the fuel - downed logs, bushes, fallen branches - built up over years and decades and then when a fire came through it was much more destructive. A little fire is good, too much fire, not so much.

Smaller, more frequent fires can be a beneficial tool and Indigenous people have known this for thousands of years but the science of these types of fires and creating these fires through cultural practices has not been very well studied. That’s where Melinda as a Native American and PhD scientist trained in cultural fire practices steps in.

Melinda explores the effects of low temperature prescribed fires (fires that are purposefully set) on plant and soil health. She and other researchers have found evidence that these beneficial fires increase plant biodiversity, can increase carbon storage in the ground, increase soil nutrient levels and make soils able to hold more water.

Melinda also looks at fire use as a cultural practice that has been passed down for generations within Native American communities. From the San Carlos Apache tribe, she has a unique background in both traditional ecological knowledge and modern environmental science. She is bridging the gap between Indigenous practices and contemporary scientific research.

And her work doesn’t end there, she’s also involved in helping create policy - turning her science and engagement with Native American communities into new approaches for how fire is used and bringing more Indigenous people into the field.

Her scientific spark (never a more relevant SuperScientist for this): Growing up in the Southwest United States in Albuquerque, New Mexico, surrounded by various Native American tribes and nature, she developed a profound connection with nature and the environment - the forests, the rivers and deserts. “I always felt the best when I was outside. Kids are naturally curious and want to know more about the things around them and why they are that way.” Nature is really the first laboratory, prompting so many questions about nature and our place in it. Now, as an environmental scientist, she’s paid to work outdoors and is still asking and answering questions about the natural world.

University and beyond: Melinda studied at a tribal university - Haskell Indian Nations University, open to Native Americans - and was drawn to learn about the plants that Indigenous people used for medicines, food, weaving, and more. She learned about how Native Americans used fire as a tool to make those plants more common and plentiful. Grasses, for example, grow back straighter after a fire and so are better suited for basket making. The take home was that fire is a tool for stewardship of nature and Indigenous culture.

From there she completed a Masters degree at Purdue University where she studied tall grass prairies and the effect of fire on the soil, looking at how fire affects culturally significant native plants and their competition with invasive species. Utilizing research design from her restoration work as a master of science student, she completed her PhD at the University of California, Davis where she studied the eco-cultural benefits of Indigenous cultural fires, which are led with traditional ecological knowledge.

What does it take to do all of this and succeed (her ranking): hard work, creativity, curiosity, communication

What else do you need? “Culture - there is so much to learn from the experiences and knowledge of local Indigenous communities, when done so respectfully.”

Her Heroes: “Past and future Indigenous scientists. Our elders and my ancestors have been practicing what I research for thousands of years. Young people also inspire me to pass these lessons forward.”

Her Top Tip: “Surround yourself with people who both inspire and challenge you to be the best that you can be.”

Why is it important for science to be diverse? “It allows for many different types of science to come together. Science can be very siloed, people typically work solely within their own field. The future of science is interdisciplinary and involves many different professions, not just scientists. In my work for example, I also engage policy makers and government agency implementers. The larger scale challenges that we are going to face in coming decades will need to be approached through an interdisciplinary lens.

As a woman of color our knowledge and ideas haven't always had a space in scientific decision making, or in how we go about learning science, and training the next generation of scientists. The current atmosphere creates opportunities for more women and more women of color to study and lead in the sciences.

As an Indigenous scientist studying fire, I see how my ancestors and relatives passed down their scientific knowledge and practices that sustained our lifeways for generations, for millennia. So, having the opportunity to educate people about this helps build the visibility of Indigenous people in science and amplifies the value of traditional ecological knowledge.”

Her least favourite part of science: “Having to reiterate why it is that we need good fire in the first place and that my ancestors knew these lessons. These knowledges are constantly having to be validated by other scientists.”

Her favourite part of her job as a scientist: I have three 1)Connecting with the land. I get to connect to the land as a regular part of my job and map out where to place fire in the areas that need it. I also get to then work with people to teach about the science of fire and good fire. I see the landscape before fire and then the fire itself - the physics and chemistry and see what it does to the environment. Then I come back two weeks later, three months later, six months later, nine months later and see, the positive effects of these burns.

So, if fire is telling a story, I get to see all parts of that story played out on the landscape and the plants and animals that come back after fire. I don't have one conception of fire - wildfire, catastrophic fire, I have these different experiences of good fire that I've played a part in bringing back to our lands. So being able to see that evolution of fire and fire’s story told through the landscape is my favourite part.

2) But equally, my favorite part of what I do is collecting plant and soil samples because I know it's going to answer scientific questions and tell me if and how fire is improving and protecting our environment. I get to be an Indigenous scientist, centering and uplifting my cultural knowledge while also informing and answering scientific inquiry.

3) Finally, what I love most about what I do is meeting different people, those who are interested in what it is that fire does and what good it can do. I also get to share how Indigenous peoples have used and understood the science of fire for thousands of years.

Melinda’s work has been supported by: The National Science Foundation, The Ford Foundation, The Mellon Foundation, The Switzer Foundation, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The Cobell Foundation, The United Auburn Indian Community Scholarship, Humboldt Area Foundation, The American Indian Science and Engineering Society, The Southwest Climate Adaptation Science Center, The UC Davis Institute of the Environment, and UC Davis Graduate Studies.

Hopefully this and the work of Melinda has changed your understanding of fire. You can read more about her work and the work of other fire scientists at…

https://news.ku.edu/2023/07/05/spreading-gospel-good-fire-grass-burning

https://www.switzernetwork.org/fellow-stories/melinda-adams-spreads-gospel-good-fire

https://www.ucdavis.edu/news/climate/melinda-adams-flame-keeper